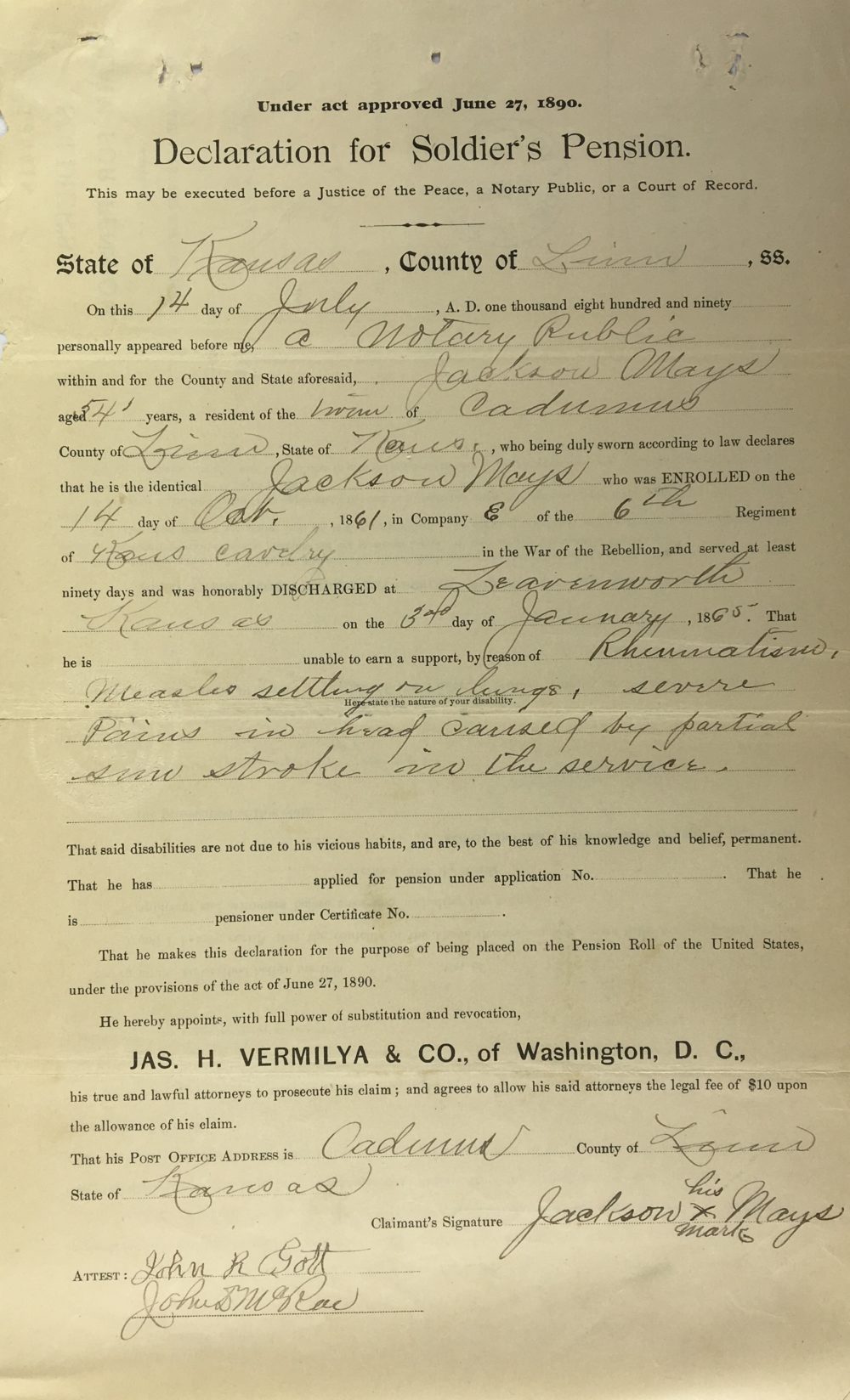

Introduction: The last blog, Valentine Seeser – Living on the West Bluffs of Kansas City, described the living conditions of the West Bluffs area where Valentine Seeser lived and the rather precarious and unhealthy environment of his communtiy. This genealogical adventure began with his appearing in police court due to the unsanitary conditions of his home. Valentine would find his family in the direct line of urban progress.

This blog is the fourth installment focusing on the urban renewal plans of Kansas City to remove Valentine’s community permanently replacing it with a public park.

A City Beautiful – Kansas City’s Urban Renewal Program

As early as 1887, plans were being hatched to rid the city of the blight along the bluffs. The idea was to transform this “eye-sore of Kansas City” into a “grand public park” with gardens of “green terraces” and “picturesque grottos” with “sparkling fountains.”

In place of the unsightly shanties a serene space was envisioned with “charming walks and shady nooks” enhanced by “nice drives and park policemen” guarding “pretty nurse girls and what not.”

The current condition of the area with “a thousand shanties and tenement houses which tremble in every fierce gale of wind” dotting the landscape carried a “very bad impression” of the city. [1]

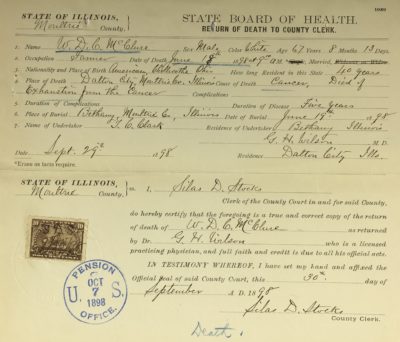

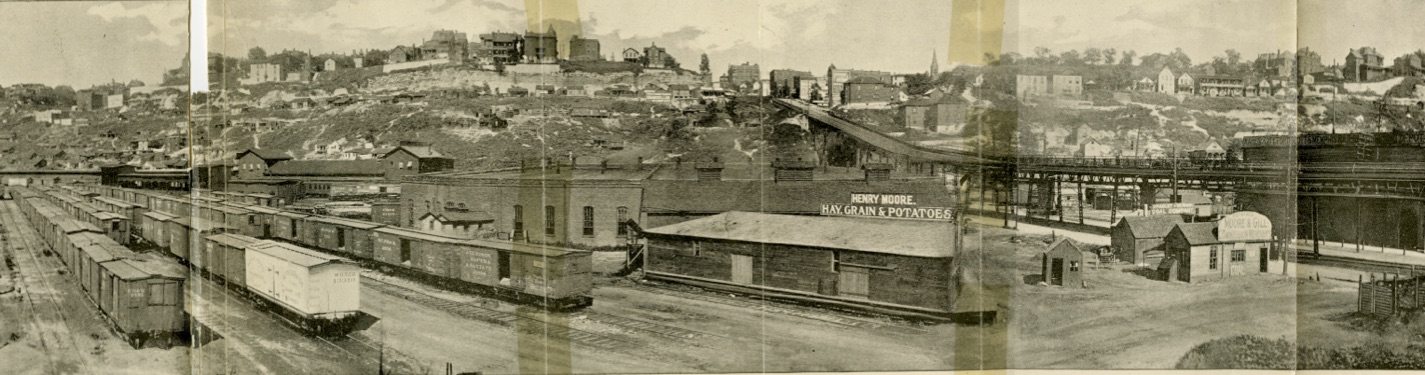

West Bottoms Kansas City

Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri

The Sanitation Department Investigates

Sending the sanitation department to investigate the area in 1890 may have been designed to gain evidence in support of condemning those living in the area. The Kansas City Times reported the sanitation review “would prove a great boom” for improving the area as the sanitation officials had concluded the bluff was an absolute “nuisance to all who live along it.” Developing the bluffs would “wipe out the existing condition of things” converting the place “as odorless as a new stone jug.” [2]

Formal Plans of the Board of Park and Boulevard Commissioners

In October of 1893 formal plans were announced in a published proposal made by the Board of Park and Boulevard Commissioners of Kansas City to turn the bluffs into a “dignified improvement” by reverting it back into it’s more natural state in “place of an eye-sore”. Boasting the cliff area was “possessed of great natural beauty,” the rocky outcrop had potential, commanding “broad and sweeping views of rare beauty.” [3]

The commissioners argued, the present condition of the cliffs was an embarrassment as “thousands of tourists annually passed through the city” after arriving at Union Depot, only to look up towards the East and see the unsightly hovels and billboards dotting the landscape. Such a situation “undoubtedly has caused much unfavorable and, in part, unjust comment of our city.” [4]

West Bottoms & Bluffs – 1895

Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri

The view looking over the “great railway yards in the Bottoms, the Missouri River,” and the “great manufacturing establishments” would “always be interesting” providing a “comprehensive idea of the business interests and the factors upon which the greatness and prosperity the city” depended on. It was naturally a convenient form of civic advertising if only it were developed correctly. Furthermore, placing a “recreation-ground” on top of the bluffs on account of its “high location” commanding “broad and sweeping views of rare beauty” would make it “famous the country over.” [5]

Naming the plan the West Terrace area, it was to extend from 7th to 17th streets on top of the bluff and down to Freight Street below. By “removing the shanties” planting vines and some trimming, it would become much “more agreeable than now.” Drawings showed special lookouts projecting from the bluff, with a new boulevard where “carriages may drive and stop to get the grand views obtainable” with a massive stone stairway leading to a park above. [6]

West Terrace was to be a part of a massive and bold plan to create a park and boulevard system by the board of commissioners to encourage economic growth and remove blighted areas throughout the city. Planners had little concern for the plight of the “slum-dwellers” found in the path of redevelopment. The upscale Quality Hill area above the bluffs had increasingly become less desirable and land values depreciated as the blight encroached upward along with the rising smells of the stock yards and smoke from the bottom land. The only thing needed was for the city to acquire the land. [7]

Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri

People Actually Lived There?

As plans developed for urban renewal, the city did make some effort in cleaning the bluffs area. A few months after Valentine’s court appearance, Superintendent of Buildings, one Mr. Love, had begun “an active warfare against the squatters” along the West Bluffs. In December of 1894, Deputy Hogg deployed an agent to tear down a shanty at 804 Lincoln Street, with a promise this was only the beginning with more to follow in the next few days. Interestingly the shanty that was torn down was located “close to the abandoned power house of the Elevated Road, near Eight Street” fitting the area described for Valentine’s location in 1893. [8]

The Kansas City Times published an article reviling the condition of the bluffs and the inhabitants who lived there. Calling it the “filthiest part of Kansas City” and a “popular resort for dyptheria [sic] and typhoid fever germs.”

Superintendent of Buildings Love took a tour of the area in December of 1894 to investigate the sanitary condition of the area. According to Love, he planned to recommend to the city council a significant part of the buildings to be torn down, as “their presence means the further continuance of disease in that vicinity.”

9th Street Cable Car Incline – West Bottoms

In many places one could stir the soil with a stick setting loose noxious gasses “of the most villainous description.” Of course the paper pointed out, the smell was scientifically known to be the result of the types of organisms that brought on disease.

Cess Pools – Ooze – Disease

When the “cliff dwellers” used “vaults and cess pools” for human refuse, the receptacles invariably leaked with the “whole soil” of the bluff becoming defiled. Health Officer Waring explained if this was not enough, along the base of the bluff springs of “sparkling water” were used by hundreds of people for drinking, washing, cooking, and everything else. After testing the water he found it was also contaminated with “deadly disease.”

Waring was convinced a recent breakout of diphtheria at a local school immediately above the bluff area was a result of the “filthy condition” of the bluffs and exposure to the unsanitary conditions.

Love felt much of the existence of disease was derived from those living in the shanties. Describing the inhabitants as squatter’s who were “accustomed to throw their slops and refuse” upon the ground wherever it was the most convenient. This resulted in the soil appearing black and “oozy with decaying organic matter.” Love was convinced the area demanded “immediate attention” particularly the open and leaking vaults.” [9]

Evictions Planned

The Board of Health made plans to begin evictions of residents along the bluffs that winter, but stopped short considering is was “uncharitable to drive poor people from shelter” during the winter. Dr. Waring made another inspection trip to the bluffs in the spring of 1895. Apparently many of the “squatters” had cleaned up their places well enough to prevent being forced to leave. [10]

The Kansas City Star, encouraged removal though, with the opinion the city “cannot always tolerate the spectacle of these unsightly hovels on the eminence overlooking” the city. Further, it was suggested the inhabitants of the “wretched shanties” would be much more comfortable, have more room, and a “wider breathing space” somewhere else. Calling on the Board of Health to clear the area as soon as possible in order to impose any further “infliction of hardship” on the “poor families who cling to their squalid hillside homes.” [11]

Condemnation Proceedings Against The Bluff Dwellers Begin

On 6 Oct. 1896, the Kansas City Times reported, after eighty days of deliberation, a condemnation jury returned a verdict to Judge Scarrit, for compensation for parcels of land to be taken between 7th and 17th Streets. Compensation was to be awarded for damages as well. The jury considered 13,000 tracts of land for possible benefits to be awarded. Damage provisions were provided for seventy-nine owners of small houses on leased ground on Lincoln and Lafayette streets, the area where Valentine lived. [12]

In 1896 a condemnation jury approved a large sum of money to be paid by property owners to purchase the land along the bluffs, and by the spring, 700 property owners were to be served condemnation notices. [13]

However, an anti-park group called the Taxpayer’s League began petitions against the development opposing the high costs involved and complained the area was unsuited for recreation and designed primarily for ornamental use only.

West Terrace Park

Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri

As late as December 1898, the houses on the bluff remained. One writer noted that year, if only “these beetling bluffs were cleaned” and “the suggestions of squalor and poverty removed” those traveling to Kansas City would not “feel the jarring sense of ugliness” as they left the trains at Union Depot. One writer complained the “unsightly and repulsive bluffs, covered with miserable shanties should be blotted out” as they were like “leprosy sores upon the face of the city.” [14]

The following year the league’s ordinance to repeal the West Terrace Park failed. The city placated the league by scaling down the size of the park as the group agreed not to bring forward their complaint to the Missouri Supreme Court. However, the court case moved forward after a complaint was made by a resident over his proposed settlement. Finally, the court ruled in favor of the city, which allowed the demolition plans to finally materialize.

Day of Demolition

The city did not acquire the land that lay between 8th and 17 streets until 1903 and not until 1904 did construction finally begin. The Kansas City Star reported on August 22, 1904, park board laborers, under the direction of W. H. Dunn, Superintendent of Parks, began tearing down the “shacks and dwelling houses” on the West Bluff. A long line of “about twenty teams” extending from Eighth to Twelfth streets along Lincoln Street swarmed over the hillside like army ants and began the demolition. [15]

Even though “occupants of the buildings” had adequate notice given to them to move, “more than one family this morning had to set their furniture in the road” while the park workers started on the roofs ripping off shingles. The teams of workmen were described by the paper making “short work” on the shanties, whereupon by noon time, children could be seen “guarding the household effects” piled up on the ground. [16]

Was Valentine still living in the area at the time of the demolition? It’s complicated.

The next installment, explains the whereabouts of Valentine and some of the research techniques used to find him. Valentine Seeser – How to Trace One’s Travels

End Notes

- “The Bluff Park,” Kansas City Times, 27 July 1887, pg. 8, col. 1.

- “Its Sanitary Condition Bad” Kansas City, Times 11 Dec. 1890.

- “Report of the Board of Park and Boulevard Commissioners of Kansas City, Mo.” Board of Park and Boulevard Commissioners, August R. Meyer, et. al., 12 Oct. 1893, (Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co., Kansas City Missouri : 1893), 46-7, digital image, Google Books, (https://books.google.com : accessed on 6 Jun. 2018).

- Ibid

- Ibid

- ”Will Assist Nature How the Park Board Proposes to Make the City Beautiful,” The Kansas City Times, 22 Oct. 1893, pg. 12.

- Deon K. Wolfenbarger, “Historic Resources Survey of the 1893 Parks & Boulevard System, Kansas City, Missouri,” undated survey, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, pdf file (https://dnr.mo.gov/shpo/survey/JAAS026-R.pdf accessed on 6 June 2018). Cooper, Robert Neil, “Kansas City, Missouri’s Municipal Impact on Housing Segregation” (2016), Electronic Thesis Collection, 86, Pittsburgh State University Digital Commons, digital images (https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu: accessed on 6 Jun. 2018). Naysmith, Clifford, “Quality Hill: The History of a Neighborhood,” Missouri Valley Series, no. 1 (1962)13, 15, 24, Kansas City Library, Kansas City, Missouri.

- “Clean The West Bluffs,” Kansas City Times, 18 Dec. 1894, pg. 8, col. 2.

- “Diphtheria Breeds There,” Kansas City Times, 14 Dec. 1894, pg. 2.

- “The West Bluffs Squatters,” Kansas City Times, 18 April 1895, pg. 1, col. 2.

- Untiled article, Kansas City Times, 19 April 1895, pg. 6, col. 4.

- “West Bluffs Price Fixed,” The Kansas City Times, 6 Oct. 1896. pg. 8.

- “Preliminary West Bluffs Park Work Begins,” Kansas City Star, 18 May 1896, pg. 1, col. 2.

- W. H. Gibbins, “Those Unsightly Bluffs,” Kansas City Star, 6 July 1897, pg. 8, col. 2.

- “Shacks Are Being Razed,” Kansas City Times, 22 Aug. 1904, pg. 2.

- Ibid