Can an undated military artifact, with no known provenance or person associated with it, in some manner, help tell a personal experience? Better yet, could it breathe life and tell you a military genealogy story?

Very unlikely, but sometimes with a little research, such an artifact might come really close. A case in point, a billet card and how it came to help make a personal connection to a U. S. WWI soldier and his experience embarking to the European theatre in 1918.

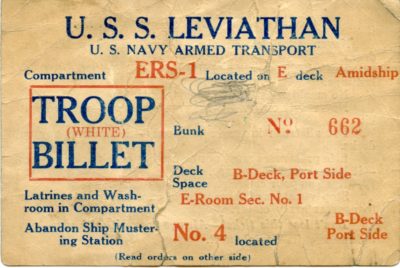

The Billet Card

The card, a family heirloom, was found among personal papers belonging to my grandfather and logically appeared to be linked to his service in the U.S. Navy in World War II.

After some quick research, the card was found to be associated with a World War I troop transport ship, the U.S.S. Leviathan and fits other known examples of similar billet cards from the same ship. These cards were issued to soldiers on troop ships, acting as identification credentials and locators for a soldier’s living quarters or “billet.” [1]

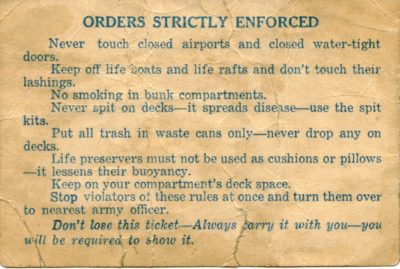

Printed in blue ink across the top is the heading, “U.S.S. LEVIATHAN U.S. NAVY ARMED TRANSPORT” followed by details of the location of a soldier’s billet and information for the location of latrines, washroom, and mustering station.

On the back are found directives and rules for troops while on board.

Who Did This Card Belong To?

A likely candidate was my grandfather’s uncle, Harry Warren Mays, who served as a private in Company K, 351st Infantry Regiment of the 88th Division in 1918. The 351st served in France, but did the regiment ship out on the Leviathan? [2]

The 351st regimental history records the entire regiment boarding in New York onto three ships, the Saxon, Scotian, and Ulysses and then set sail to France. The 88th Divisional history confirms this information noting the 3rd Battalion of the 351st Infantry boarded the Ulysses on August 15th, while the rest of the regiment boarded onto two other ships, the Saxon and Scotian on August 16th.

According to recollections of Company K’s commander, Second Lieutenant, Jack W. Long, his men boarded the USS Ulysses at the Hoboken debarkation port in New York Harbor on August 11th. Thus, all the evidence points to Mays having sailed on the Ulysses and not the Leviathan. [3]

Finding My Great Uncle Harry Warren Mays

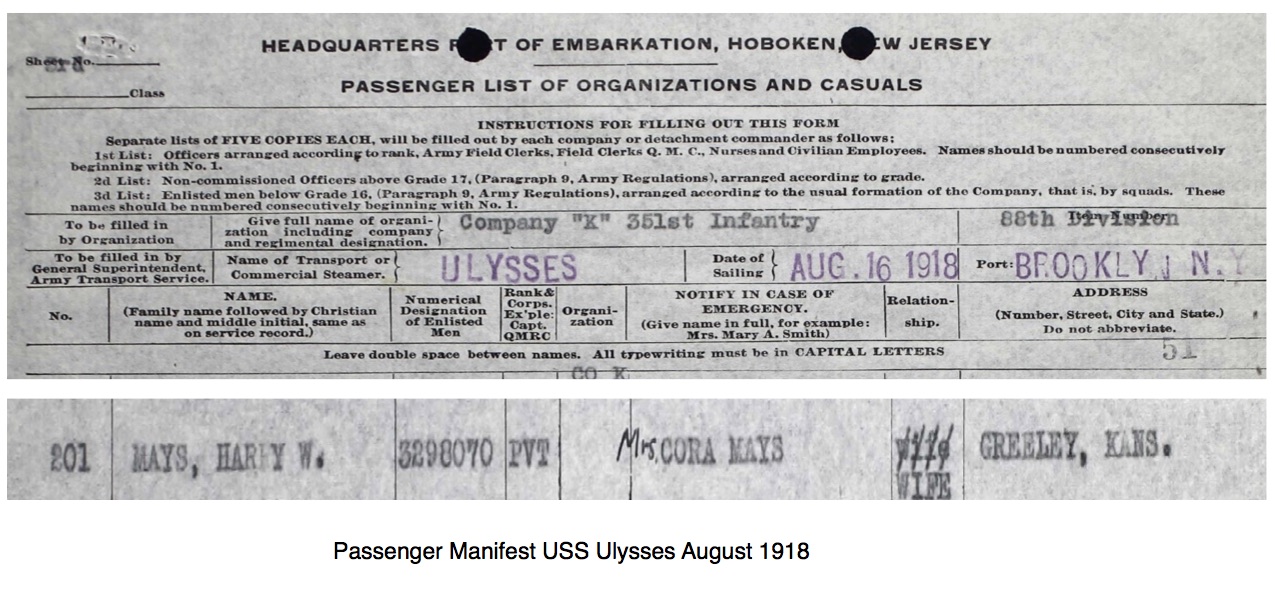

Definitive proof Mays was on the board the Ulysses, is provided by the passenger manifest. Harry Warren Mays, from Greeley, Kansas, is listed as passenger no. 201 with Company K of the 351st. According to the manifest, the men boarded on the afternoon of August 15th and sailed the next day. [4]

On his return journey from St. Nazaire France on 20 May 1919, Mays is found on board the USS Mercury, listed as passenger no. 158 with Company K of the 351st Infantry. [5]

Clearly, the Leviathan billet card did not belong to Mays and remains a mystery how he came across it or why he may have kept it as a memento.

A Billet Card Provides a Glimpse Into A Soldier’s Experience.

I was never able to ask my great uncle about his experience as a soldier, but looking at the billet card, I can imagine him studying a similar card in his stiff army uniform as he boarded his troop transport. [6]

The wide-eyed farm boy from Kansas listened intently while one of the officers from his company’s advance party escorted him to his bunk area. Looking down at the card, noting his bunk number and his deck space.

The next day, August 16, the ship engines fired up, and the troop ship made its way down the Long Island Bay. May’s could hear the regimental band playing quicksteps as the men were allowed to finally go on deck.

Joining his comrades, they swarmed and squeezed onto every inch of the ship, the lifeboats, ventilators, even the rigging, and began cheering. Someone said this was done to depress the morale of the enemy, the government wanted them to know how many doughboys were on their way to end the war. Many of the boys were midwesterners, and like Mays, they were awed while watching the New York skyline and Statue of Liberty.

It was a special day for Mays, he was finally shipping out and it was his birthday. [7]

Mays was not a young kid at twenty-four years old, and he knew his way around a farm, but he came from a small rural town, and the last few days seemed like a dream. That night, sitting on his bunk down below decks, he pulled out his new steel helmet, and looking inside his knapsack he pulled out a picture he had placed there for safe keeping.

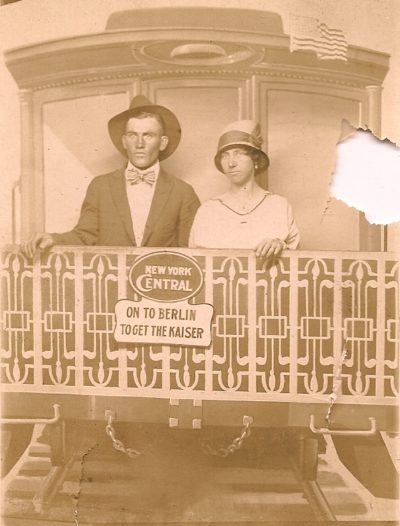

He smiled as he studied the photo of him and his newlywed Cora, he in his starched suit and her in a fancy hat. The picture, a photographer’s set, shows them standing at the back of a train, their hands resting on the back rail, with a hanging sign reading “On To Berlin To Get The Kaiser.” They had taken the photo just after getting married on the 22nd day of May 1918. Just four days later he was enlisted into the army. Having been drafted by his hometown board, he figured it would be good to get hitched before going off to war. [8]

Camp Mills Embarkation Center

In four short months of training, he found himself boarding a train with a number of his midwest buddies from Kansas and Missouri, leaving their training encampment at Camp Dodge in Des Moines, Iowa. They were heading east towards the gigantic Hoboken embarkation center.

Arriving on August 10th, after a three day journey, his regiment unloaded at the Camp Mills embarkation camp, on Long Island in New York. Immediately, Mays was awed by the massive complex, running like some well-oiled machine to make final preparations to supply and ready the troops for overseas duty.

May’s regiment assembled in tents to await inspections of their health and morale, receive essential gear, and have their citizenship status scrutinized. The U.S. Army refused to send any soldier to France without U.S. citizenship. However, naturalization courts were set up at the camps making it possible for aliens to quickly gain citizenship before boarding. The camps served as a filter to weed out any “dangerous alien, the spy, or the man of questionable loyalty.” Mays had no worries, he was a natural born citizen.

The first night of their stay at the camp, after dinner in the gigantic mess hall, the troops watched a film from the motion picture machine providing instruction on the abandon-ship drill. Mays remembered how everyone laughed as the film first showed panicked men running helter skelter when there was no orderly method used. The troops were then shown the proper organized procedures to be used and practiced those methods on the ship.

Studying his new helmet, Mays recalled how his company, under the direction of the Transportation Service at Camp Mills, was ordered to muster up in a long line and unpack all their personal effects, right there on the spot, for inspection.

Giggling, as he remembered how some of the inspectors would grab men by the seat of their pants, as they jerked down hard to make sure the seams of their breeches were in good order.

Everything was scrutinized by the inspectors, man for man. Clothing, shoes, shirts, underwear and personal effects. Rapid decisions were made whether something was “deficient” or “excessive.” Anything showing too much wear or of “domestic issue” was replaced right where they stood. Before any new apparel was handed out, the men were first ordered to strip down so they could redress with any new gear post haste.

For the first time, Mays was provided with equipment designed for trench warfare; spiral puttees, steel helmet, gas mask, trench knife, and an entrenching kit.

Hoboken Docks

On the afternoon of the third day the regiment was ready to head for the piers. First the men were loaded onto trains for a forty minute journey on the Long Island Railroad to where ferry boats awaited to transfer them to a transport ship. The ferry boats were located on the East River on Long Island, where they would then march to the Hoboken docks.

August was already becoming a peak month where nearly a half a million men were to be carried by over one thousand special trains to the ferry boats.

Mays felt a little apprehensive and electrified at the same time, having never witnessed such a sight as 3,500 soldiers of his regiment about to be loaded onto three steamships. Arriving at the docks, the men unloaded off the ferry and like ants they marched in columns down to the loading pier. Mays was transfixed, intoxicated by the sounds, smells, and the sights along the massive pier complex at the Hoboken docks.

He was moved from his daze when he heard his name as roll call was given for all the troops to line up by company. It was early in the afternoon, and the August heat seemed to roll off the wooden piers right through your boots and up into your heavy uniform.

With disbelief, Mays started to notice the tables set up by the Red Cross in a large canteen. Soldiers were taking ice cream, cold milk, and even cookies from canteen workers. The Red Cross had installed what some boasted as the largest coffee distilling plant in the world, and in a single day could dole out three tons of rolls, a ton of cigarettes, and “several hundredweight of ice cream and cookies.” Mays gratefully took advantage of the refreshments and also grabbed a few cigarettes packs being passed out, shoving them into his gear bag.

While enjoying his food and drink, Mays was handed a few “safe-arrival cards” by a Y.M.C.A worker, who encouraged all those nearby to fill out as many as they liked. The workers explained the cards would be mailed once a cablegram was received noting their ships safe arrival. Reading one of the cards, “The ship on which I sailed has arrived safely overseas,” Mays decided to address two, one for Cora and another to his parents back home. Allowed only to sign his name and no other information, he placed the two cards into his top pocket lightly patting them when he heard the command to move toward the gangplank.

Quickly downing the rest of the cold milk, Mays started gathering his gear as orders were given to once again get into company formation and prepare to get ready for boarding.

Boarding The Ship

At the gangplank, Mays watched his commanding officer take a seat at a desk and plop down a case holding the company’s service records. In front of the desk was the port checking officer and at his side the first sergeant of the company. The company was organized by squads and the passenger lists were organized in like manner. When Mays heard his name called, he responded by repeating his last name first followed by his given name and middle initial. He watched as his service record was checked against the passenger list, hearing his service number and name verified.

No soldier could board the ship without a complete paper record containing the following items; service record, individual equipment record, pay card, pay allotment record, application for War Risk Insurance or waiver, Qualification card, locator card, and sick/hospital record. Having the service records correspond to the same order of the passenger lists, proved to be so efficient, soldiers boarded in quick fashion, allowing a thousand men to board an hour at a time. May’s ship, the Ulysses, was completely loaded ten minutes shy of 5:00 p.m. after the first troops had begun loading at 2:20 in the afternoon. [9]

Once formally checked, Mays dropped his safe arrival cards into the mail bag sitting nearby. Then as he passed the desk, he was handed his billet card.

Walking up the plank, he couldn’t help gawking at all the activity and the deafening noise around him as hundreds of soldiers were being processed onto the awaiting ships. This was his first time at sea, and his ship, the Ulysses, seemed gigantic as it swallowed the troops as they walked up the plank.

At the top, he was greeted by a member of his company, requesting he look at his billet card, and told to be certain he had it with him at all times, it was like his own personal identity card. He was ordered to read the back of the card detailing the printed orders that were to be strictly enforced. Making way as others were boarding, Mays was escorted to his billeting area.

Of course everyone was excited and there was so much noise with so many soldiers speaking, it was hard to hear someone talking right next to you. Attention was ordered as instructions were given for all the soldiers to remain in their billeting area and wait for the abandon-ship drill to happen while the ship was still in the harbor.

By now it was getting late in the day and everyone was hungry and wondering about dinner. The men were grateful when given instructions to pull out their mess kits and assign men from their squads for mess details to help dish out food at the various serving stations.

The men cheered when they were told the Navy set no limit on the amount of food a man could help himself to and laughed after hearing they even had access to boxes where a soldier could deposit complaints about the food. Mays at 5 feet 8 inches tall was rather thin and could use a good meal, the Red Cross milk and cookies were wearing off.

Carefully placing the photo of he and Cora back into his bag, Mays became slightly apprehensive as he began to think of the future, and what lay ahead in France.

Notes

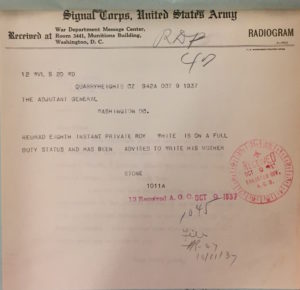

1. “World War I Collection,” Hoboken Historical Museum [New Jersey] Online Collections Database, Hoboken.pastperfectonline (http://hoboken.pastperfectonline.com : accessed on 14 June 2016); digital image, “Troop billet card for U.S.S. Leviathan, U.S. Navy Armed Transport, no date, circa 1917-1919,” Admittance card, Catalog #2006.044.0004. “NH 104240-KN USS Leviathan,” Naval History and Heritage Command, history.navy.mil (http://www.history.navy.mil : accessed on 14 June 2016); digital image, “USS Leviathan,” troop billet card, catalog #NH 104240-KN.

2. Kansas, military discharge papers, “World War I Bounty Claims Records,” box 29, #7116, Harry W. Mays, service no. 3298070, private, company K, 351st Infantry; Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas.

3. Branter, Cecil Frank, compiler, 351st Infantry, (St. Paul, Randall Company: 1919), 47 & 57; digital image, archive.org (https://archive.org : accessed on 14 June 2016). The 88th Division in the World War of 1914 – 1918, (New York, Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Company : 1919) 35-36; archive.org (https://archive.org : accessed on 14 June 2016). The Road to France II. The Transportation of Troops and Military Supplies 1917-1918, VII ( New Haven, Yale University Press: 1921), Appendix E, “Troop Sailings From New York From July 1, 1918, to Date of Armistice.” 556, U.S. Ulysses sailed on 16 Aug. 1918; digital image, archive.org (https://archive.org : accessed on 22 June 2016)

4. Manifest, USS Ulysses, 16 August 1918 [stamped], sheet 7, third class, no. 201, Mays, Harry Warren, serial # 3,298,070, digital image, “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/interactive : Outgoming > Ulyssses > 1916 Nov 12 – 1923 Jul > image 559/674, accessed on 14 April 2017); citing, NARA textual records, “Lists of Outgoing Passengers, compiled 1917-1938, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985, RG 92, Roll 601. Note: May’s name and others on the manifest correspond to the names on the Company K roster given in the regimental history, see The 88th Division in the World War of 1914 – 1918, “Roster of Company K,” 113-14

5. Manifest, USS Mercury, 20 May 1919, sheet 11, third class, no. 158, Mays, Harry Warren, serial # 3,298,070, digital image, “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/interactive : Incoming > Mercury > 1919 May 18 – 1919 May 31> image 776/829, accessed on 14 April 2017); citing, NARA textual records, “Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917-1938, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985, RG 92, Roll 199.

6. Note: The thoughts of Mays are fictional construction, but the details of the embarkation process, Camp Mills, Hoboken docks are well documented. See: The Road to France II The Transportation of Troops and Military Supplies.

7. “Military Rites for Sheriff Harry W. Mays.” The Anderson Countian (Garnett, Kansas), 7 October 1948, pg. 1 & 8; microfilm publication, reel # G494, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas.

8. “Jackson County Recorder of Deeds Web Access – Marriage,” digital image, Jacksongov.org ( http://records.jacksongov.org/Marriage/SearchResults.aspx : accessed on 30 May 2017), license & return, 22 May 1918, entry for Harry W. Mays – Gertrude C. Pratt, #79114, [ book 72, pg. 607 ]. World War I Bounty Claims Records, Harry W. Mays.

Illustrations

Photos of the Hoboken Piers, digital images, Brandon M. Cooper, June 2017, adapted from The Road to France II. The Transportation of Troops and Military Supplies 1917-1918, VII; Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

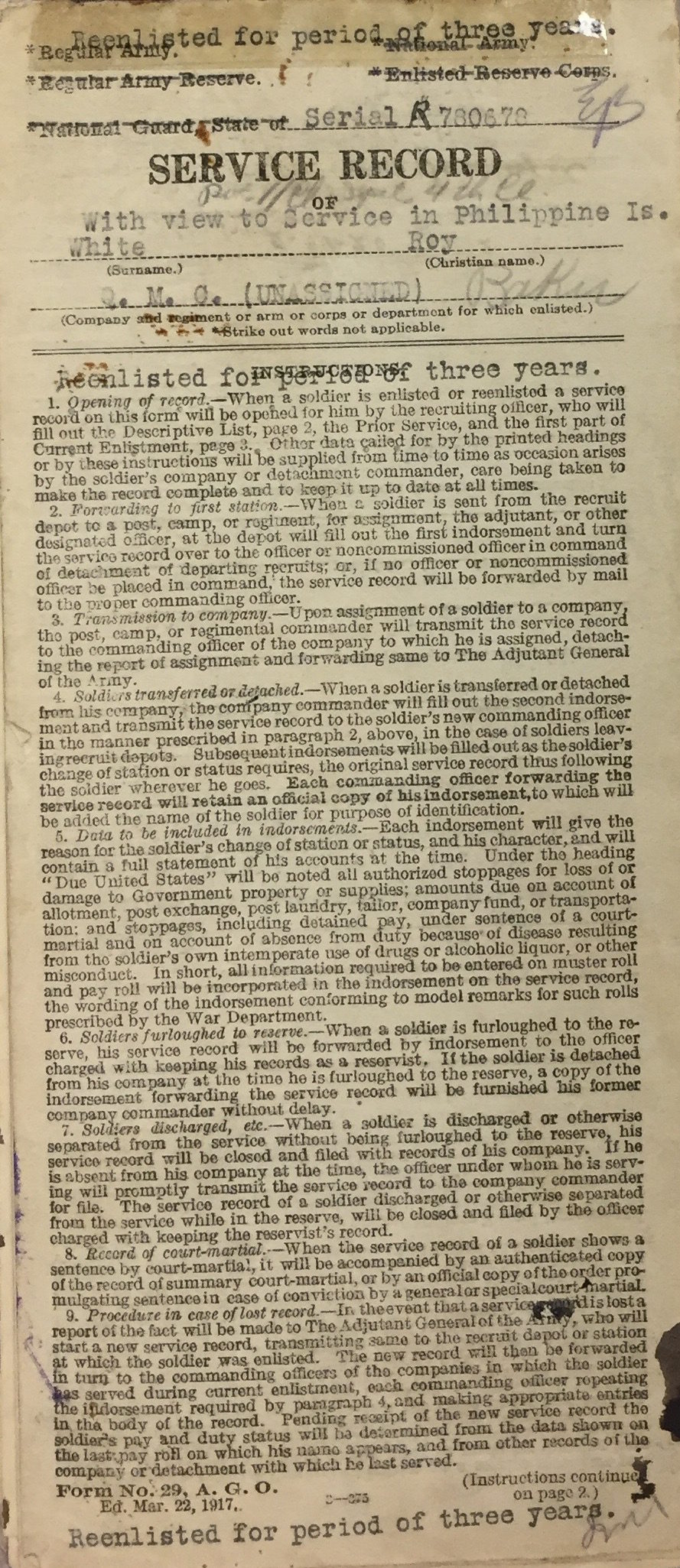

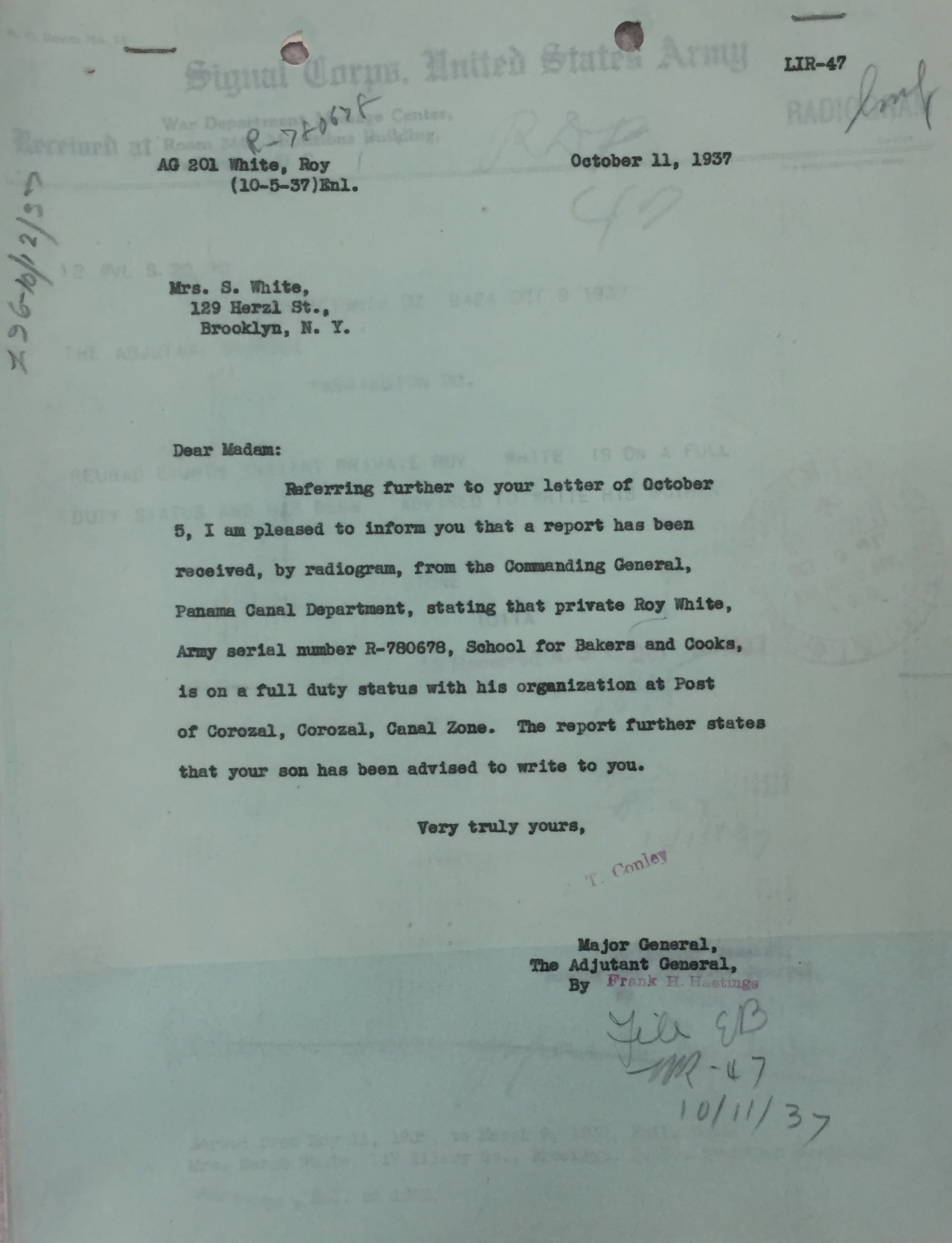

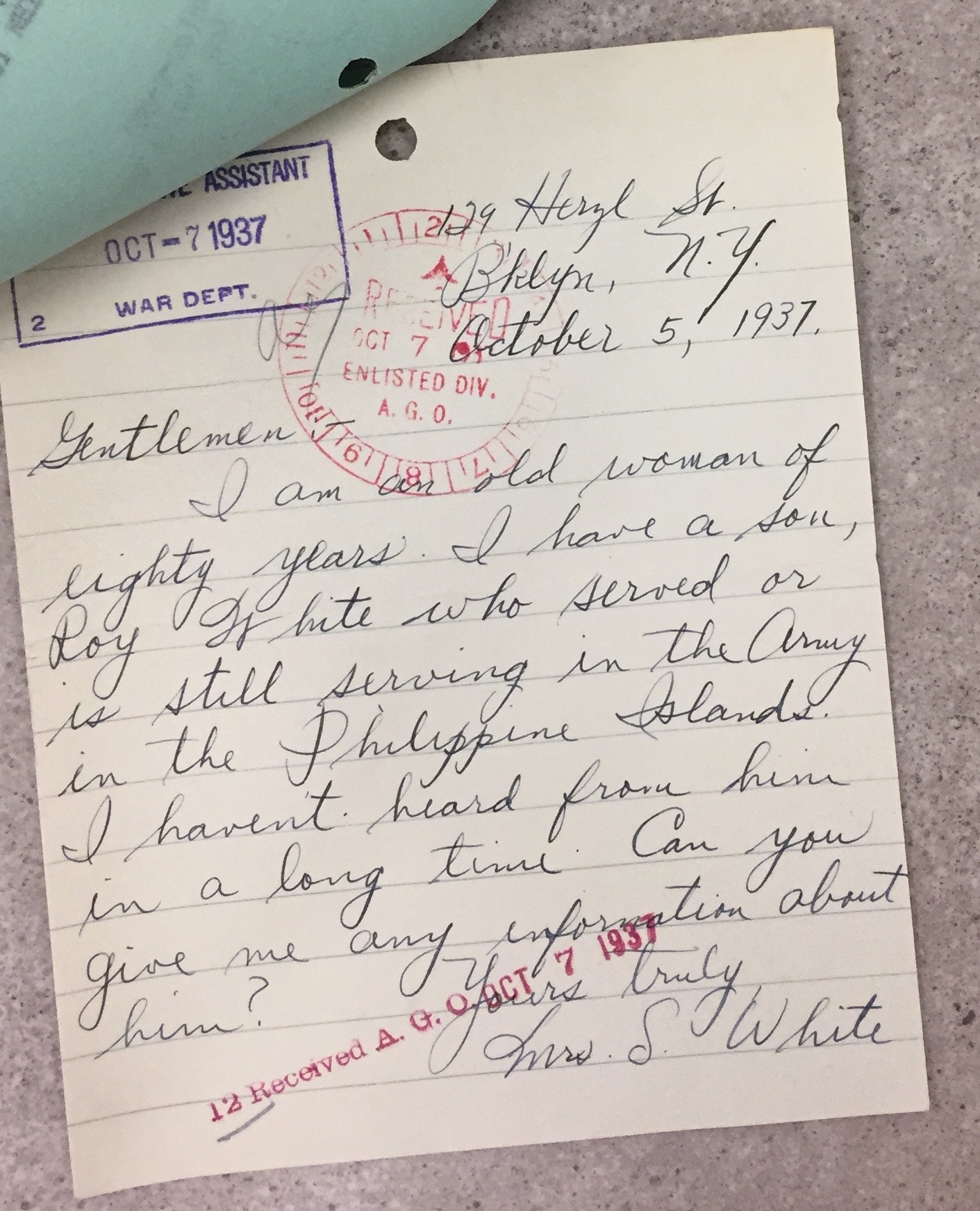

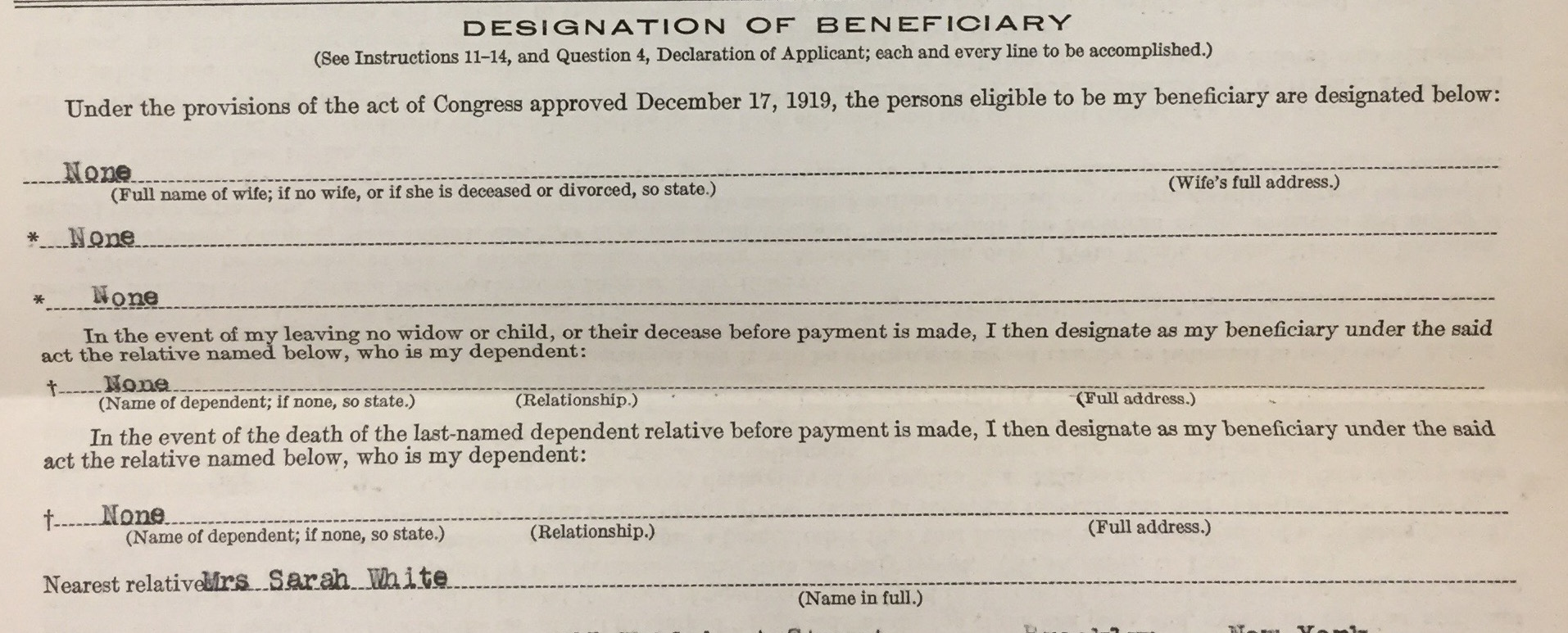

I have always wanted to look at my grandfather’s naval file, and, at the time, I was working on a research project for a client attempting to discover documentation of a family. This family had remained very elusive with very little certainty of their whereabouts or relationships. However, one of the family members served in the military for thirty years and his discharge date made his files public record. Why not request his records too, they may hold family clues.

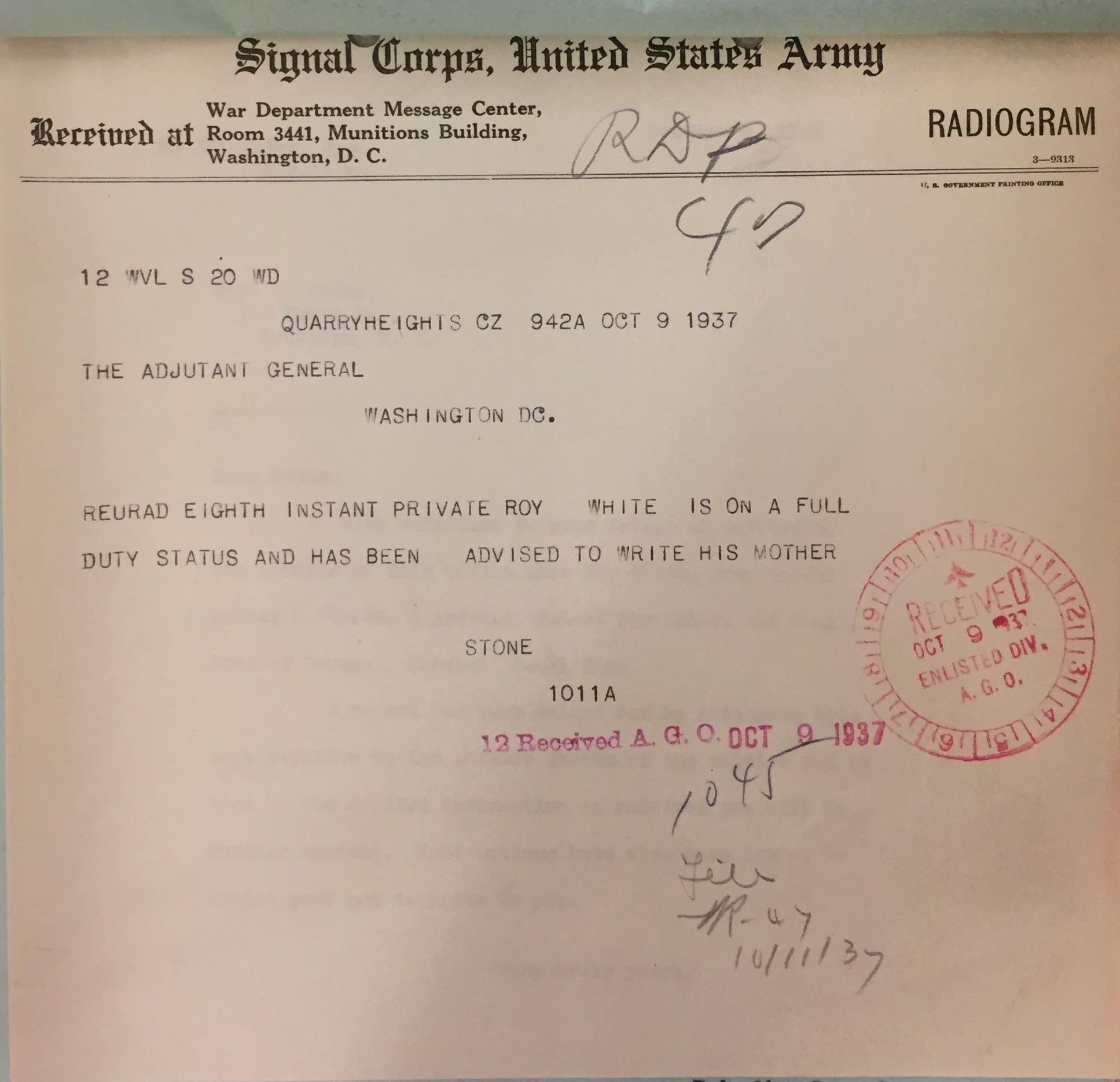

I have always wanted to look at my grandfather’s naval file, and, at the time, I was working on a research project for a client attempting to discover documentation of a family. This family had remained very elusive with very little certainty of their whereabouts or relationships. However, one of the family members served in the military for thirty years and his discharge date made his files public record. Why not request his records too, they may hold family clues. Barely thirty minutes later, I was told by the front desk personnel “we have found the files of your army sergeant.” A research room archivist soon appeared with a photocopy of the sergeant’s index card showing his service record number. I couldn’t resist asking how in the world they found his records so quickly, only having his name and a birth date.

Barely thirty minutes later, I was told by the front desk personnel “we have found the files of your army sergeant.” A research room archivist soon appeared with a photocopy of the sergeant’s index card showing his service record number. I couldn’t resist asking how in the world they found his records so quickly, only having his name and a birth date.

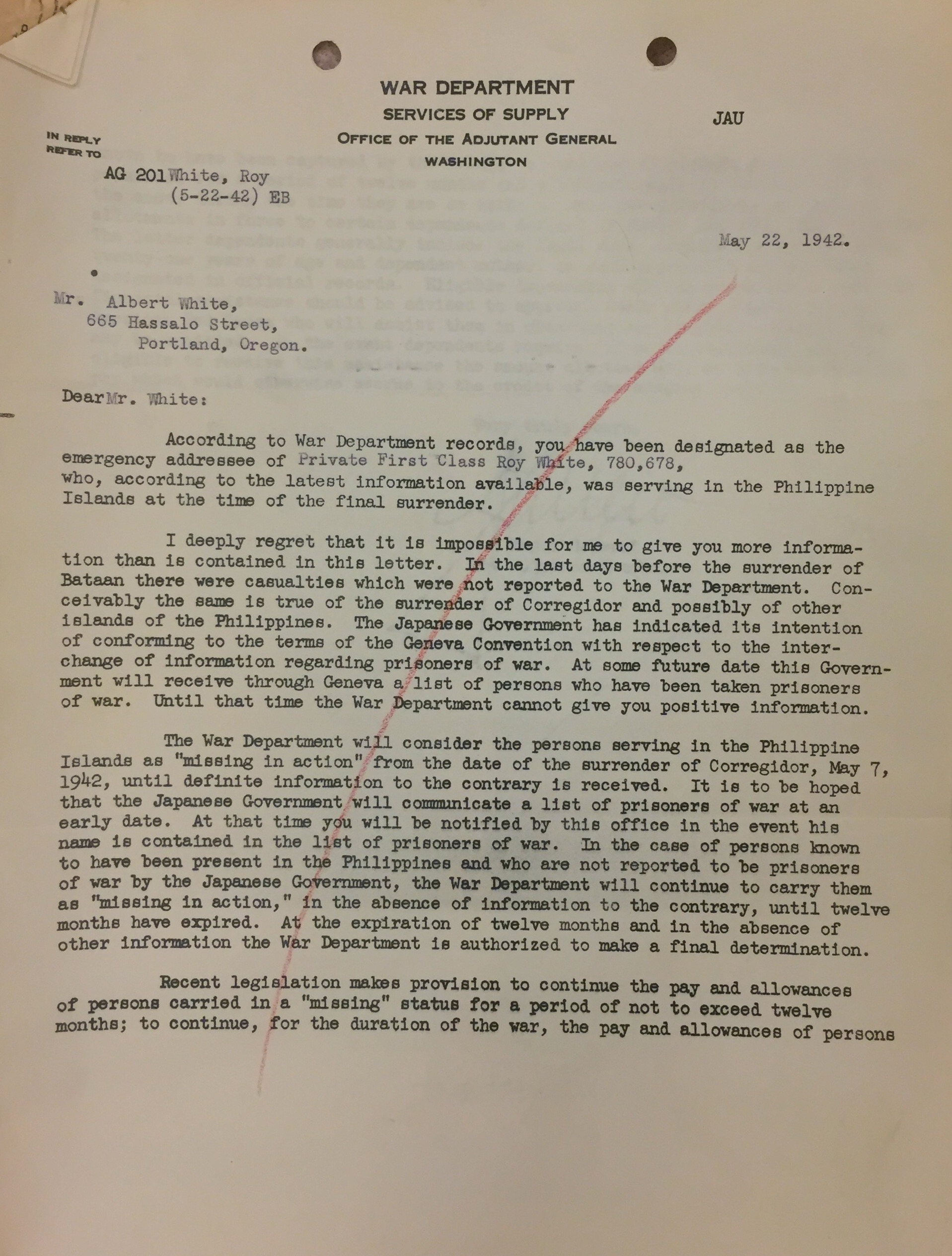

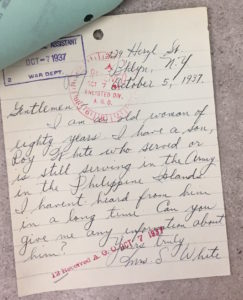

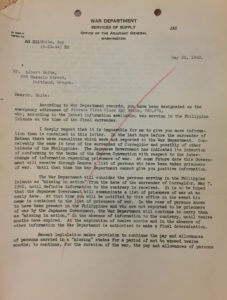

In a very formal manner, the letter warned, the War Department was not able to provide any “positive information” concerning both casualties and prisoners of war during the surrender of Bataan, Corregidor, and “other islands of the Philippines.” And, persons serving in the Philippine Islands would be classified “as ‘missing in action’ from the date of the surrender of Corregidor, May 7, 1942, until definite information to the contrary is received.”

In a very formal manner, the letter warned, the War Department was not able to provide any “positive information” concerning both casualties and prisoners of war during the surrender of Bataan, Corregidor, and “other islands of the Philippines.” And, persons serving in the Philippine Islands would be classified “as ‘missing in action’ from the date of the surrender of Corregidor, May 7, 1942, until definite information to the contrary is received.”