My wife was planning a business trip to St. Louis, Missouri, so on a whim, I tagged along, planning to visit the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). Part of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the NPRC is the central repository of personnel related records for both civilian and military services of the United States.

I have always wanted to look at my grandfather’s naval file, and, at the time, I was working on a research project for a client attempting to discover documentation of a family. This family had remained very elusive with very little certainty of their whereabouts or relationships. However, one of the family members served in the military for thirty years and his discharge date made his files public record. Why not request his records too, they may hold family clues.

I have always wanted to look at my grandfather’s naval file, and, at the time, I was working on a research project for a client attempting to discover documentation of a family. This family had remained very elusive with very little certainty of their whereabouts or relationships. However, one of the family members served in the military for thirty years and his discharge date made his files public record. Why not request his records too, they may hold family clues.

Not expecting much, having only the veteran’s name and birthdate, I couldn’t loose out by trying. Three days prior to our travel date, I found the “National Archives at St. Louis” website and filled out a request on line for two files, the career veteran and my grandfather’s navy service records.

Arriving At The NPRC

I walked into the NRPC at 11:00 in the morning, naively thinking I could stroll in, request my order, and view the files. However, I was stymied at the front desk of the Archival Research Room. The woman at the desk politely explained they receive hundreds of e-mail requests a day and normally there is at least a three week processing time. After confirming my original request, she gave me hope when she said, “I can attempt to make an expedited order.”

While I waited in the front lounge area, I began reading a display explaining the loss of a large percentage of military files from a catastrophic fire in 1973. My hopes dimmed a bit.

Sometimes though, the stars aline and you just get real lucky doing genealogy work.

Barely thirty minutes later, I was told by the front desk personnel “we have found the files of your army sergeant.” A research room archivist soon appeared with a photocopy of the sergeant’s index card showing his service record number. I couldn’t resist asking how in the world they found his records so quickly, only having his name and a birth date.

Barely thirty minutes later, I was told by the front desk personnel “we have found the files of your army sergeant.” A research room archivist soon appeared with a photocopy of the sergeant’s index card showing his service record number. I couldn’t resist asking how in the world they found his records so quickly, only having his name and a birth date.

“It helped your guy was a lifer, and his files were in a section of the building unaffected by the fire.”

In contrast, my grandfather’s naval records should have been easy, since I had his birth date, serial number, and discharge date. But it took another full day to view his files.

After watching a powerpoint presentation over the research room protocols and signing a “Reference Service Slip,” I was able to view the personnel file of my army sergeant.

Held in a long brown folder, a good three inches thick bulging with records, I held my breath, not really knowing what to expect. As I unfolded and turned over pages, the service records provided evidence of the sergeant’s parents and siblings, including addresses, helping to finally locate the whereabouts of the family and establish family relationships.

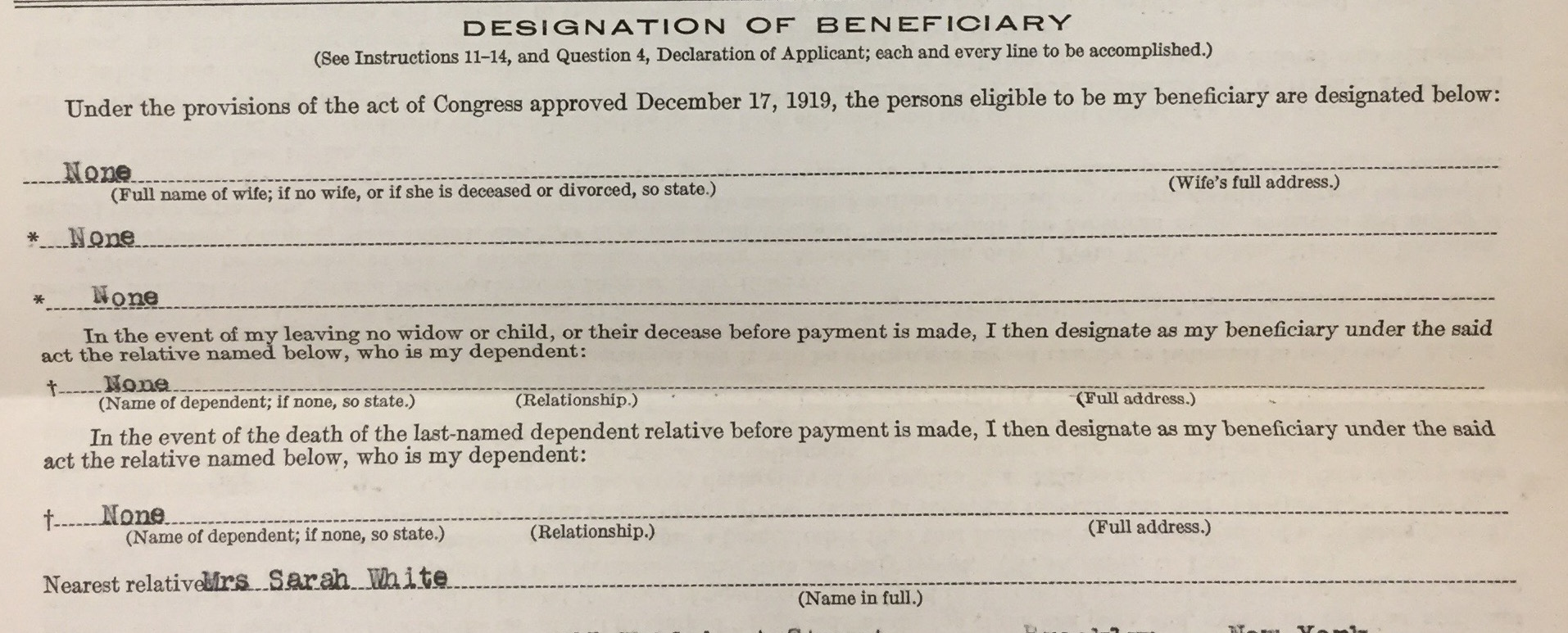

On numerous occasions, when either enlisting or reenlisting, service men would fill out insurance forms noting the names and addresses of beneficiaries names, emergency contact information, or nearest relatives.

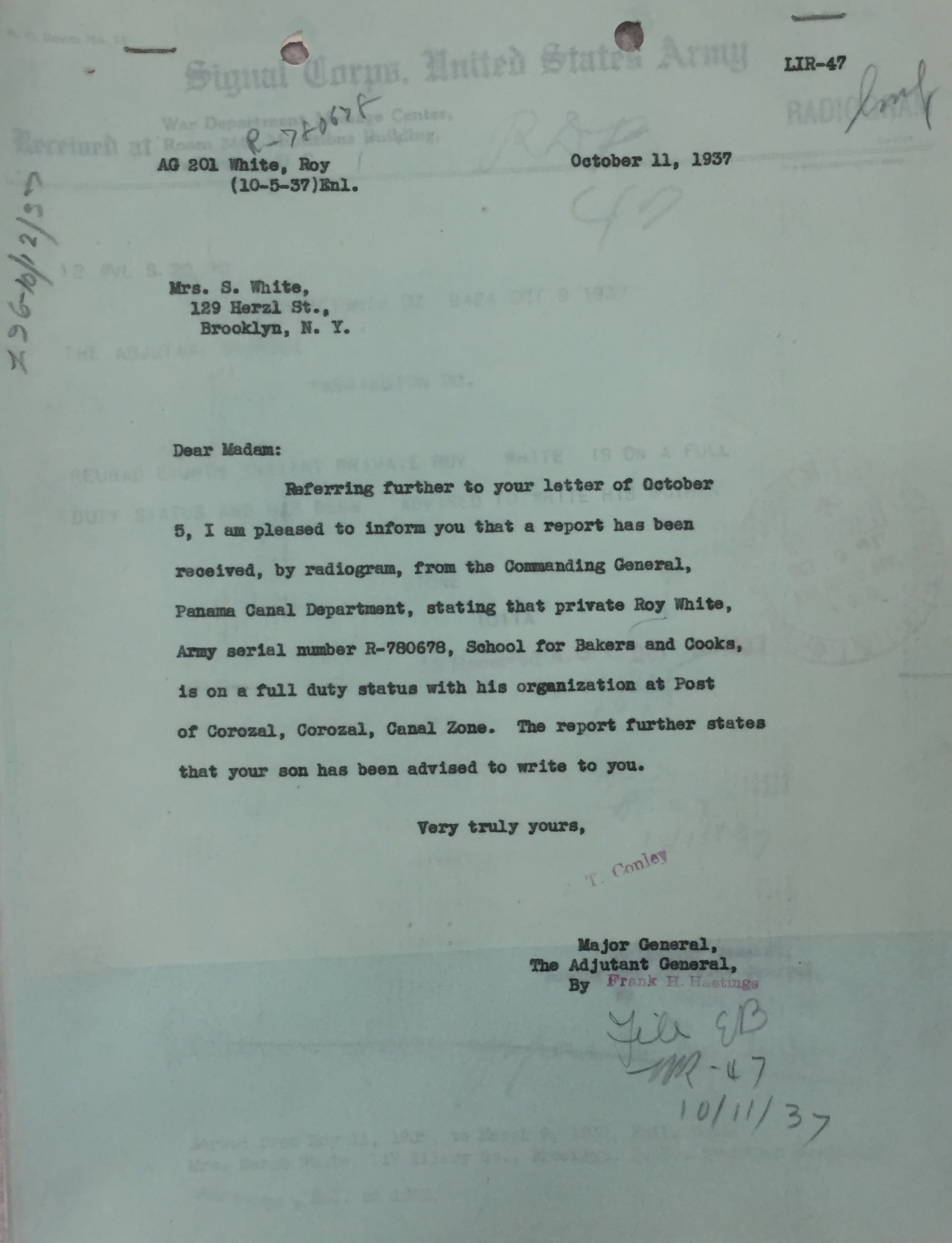

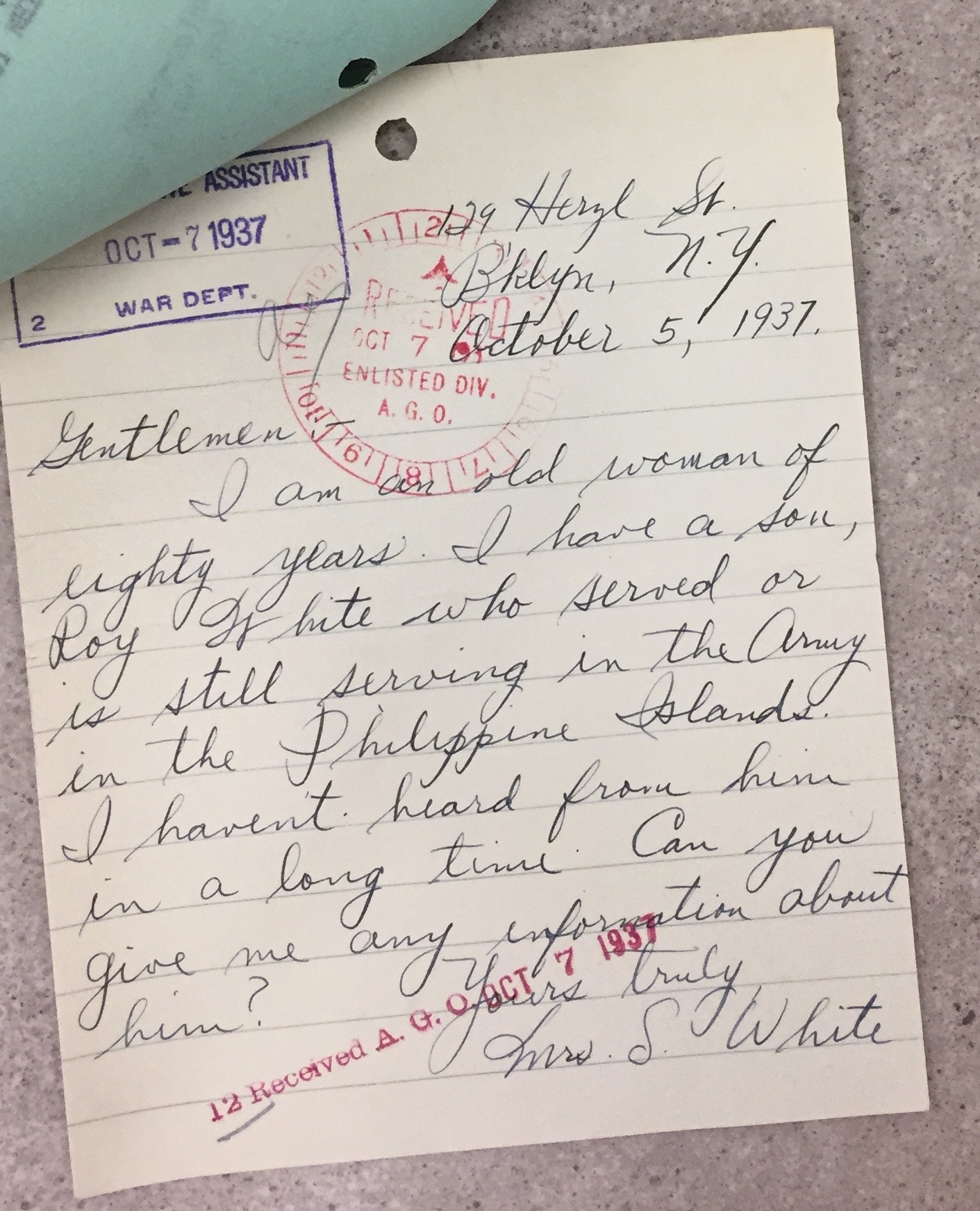

Then, occasionally, you find a gem amongst the papers. In 1937 a mother wrote a personal letter to the War Department in hopes of finding her son whom she had not heard from.

I am an old woman of eighty years. I have a son, Roy White who served or is still serving in the Army in the Philippines Islands. I haven’t heard from him in a long time. Can you give me any information about him?

Mrs. White Gets a Response

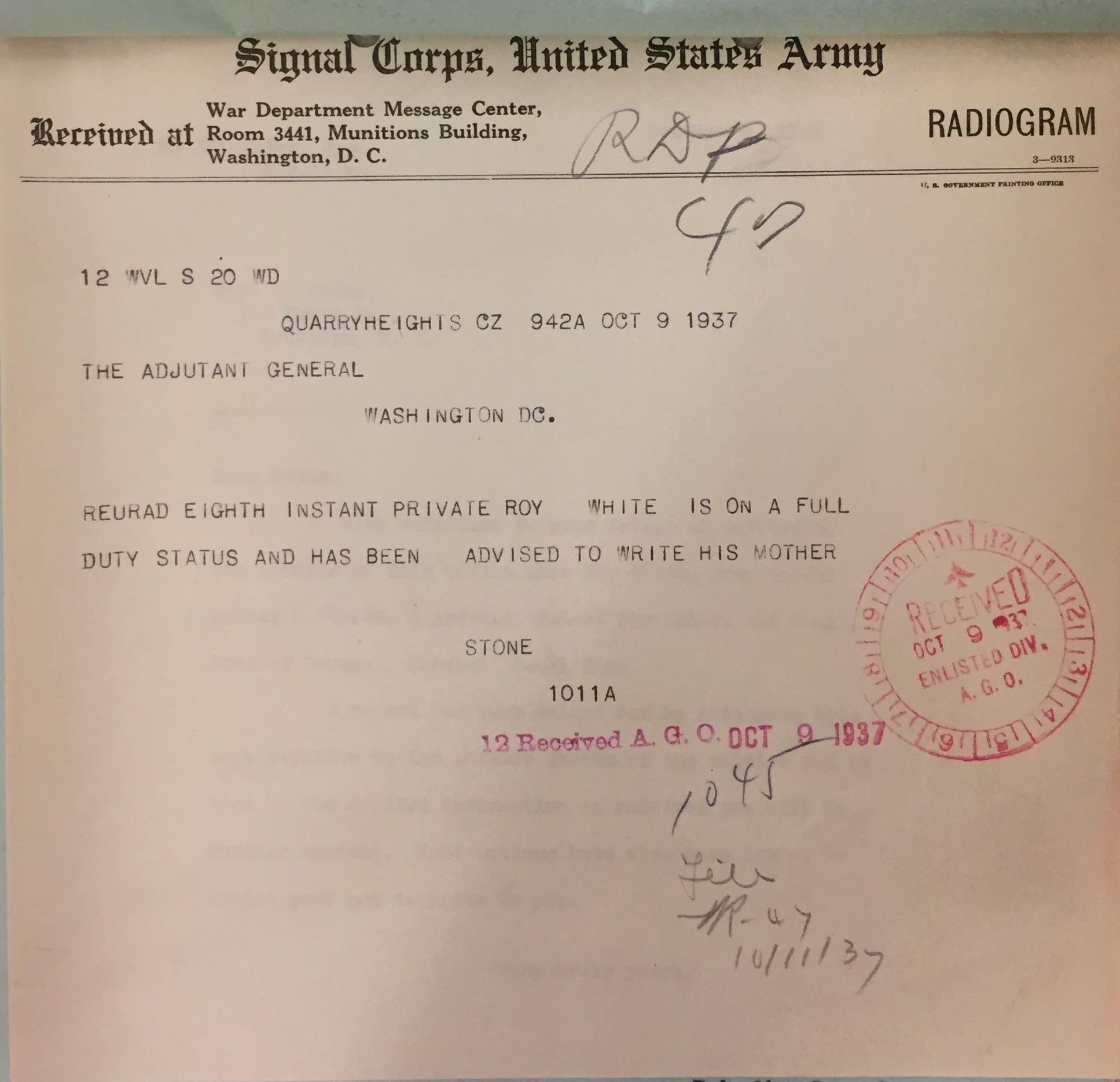

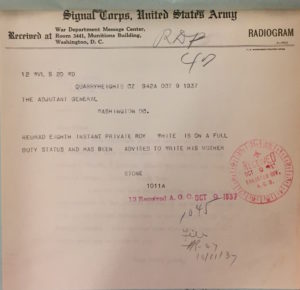

Six days later, the Adjutant General responded to Mrs. White with good news. A “report has been received, by radiogram” that her son was on full duty status with “his organization at Post of Corozal, Corozal, Canal Zone” in Panama attending school for bakers and cooks. Her son “has been advised to write to you.”

The original radiogram is included in the service file.

War Department Radiogram

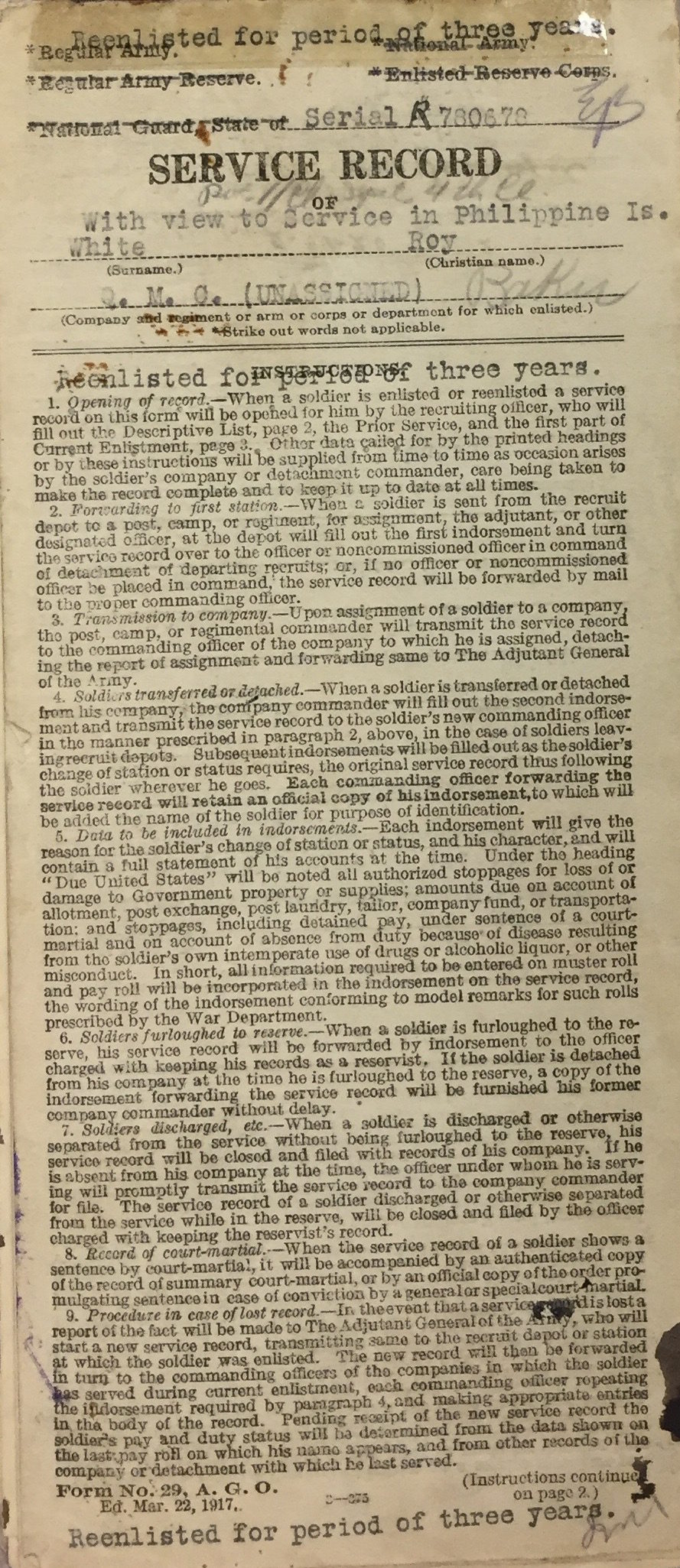

White had served in the Philippines as early as 1920. Records indicated he had reenlisted in the army in 1939 for three years, arriving in the Philippines in late October 1939. But, by 1941 it seems his whereabouts was once again uncertain during the outbreak of the War in the Pacific.

White Gets Lost Again

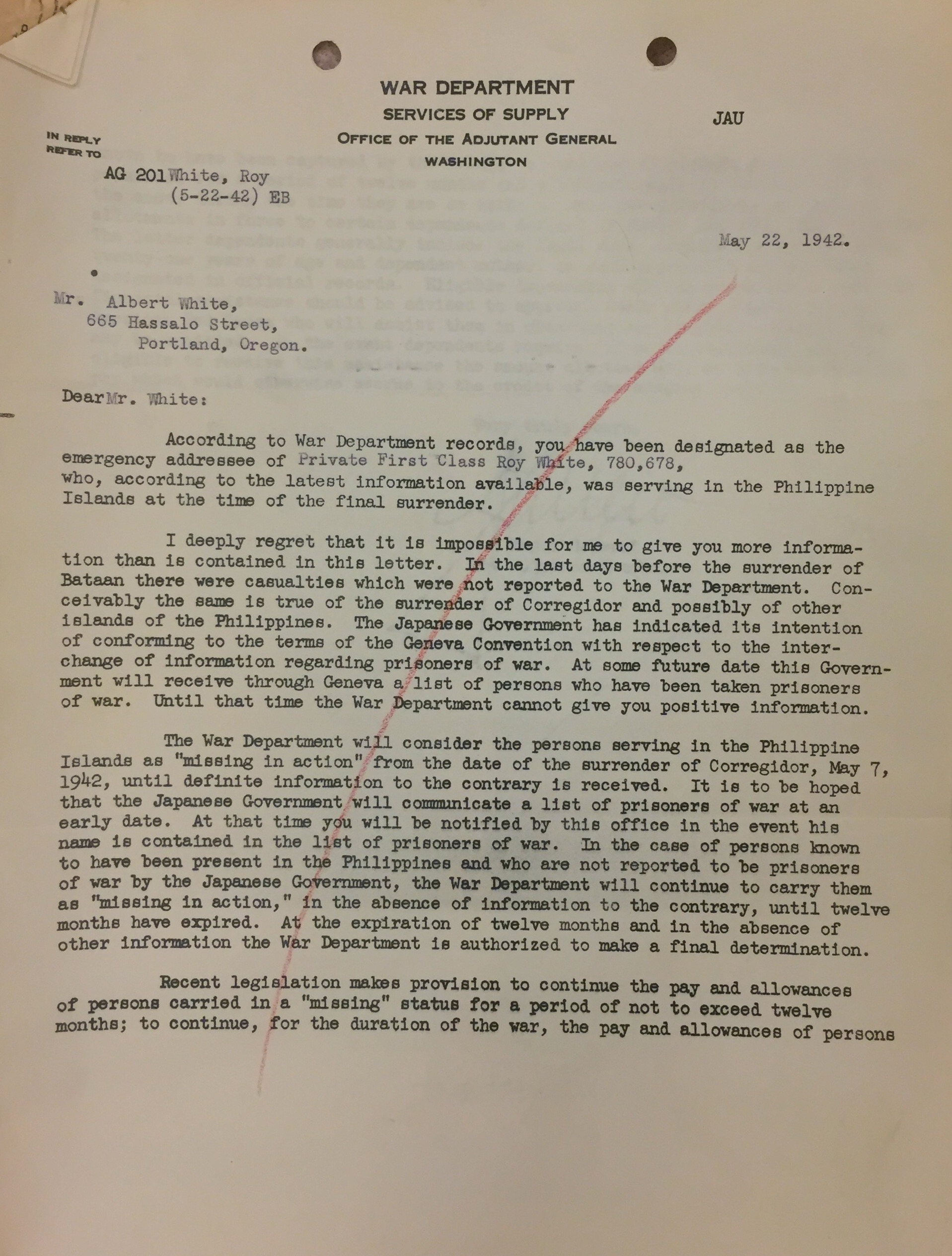

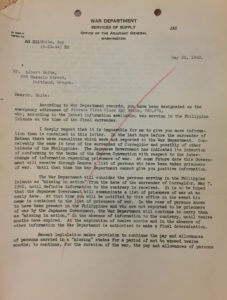

Found in the service records is a typed form letter, most likely sent to many families, concerning the surrender of U.S. forces in the Philippines to the Japanese. Dated 22 May 1942, White’s brother, having been designated as the emergency addressee, was mailed the form letter from the Adjutant General’s office. The letter provides a glimpse to the uncertainty and fears from a chaotic time in the war.

In a very formal manner, the letter warned, the War Department was not able to provide any “positive information” concerning both casualties and prisoners of war during the surrender of Bataan, Corregidor, and “other islands of the Philippines.” And, persons serving in the Philippine Islands would be classified “as ‘missing in action’ from the date of the surrender of Corregidor, May 7, 1942, until definite information to the contrary is received.”

In a very formal manner, the letter warned, the War Department was not able to provide any “positive information” concerning both casualties and prisoners of war during the surrender of Bataan, Corregidor, and “other islands of the Philippines.” And, persons serving in the Philippine Islands would be classified “as ‘missing in action’ from the date of the surrender of Corregidor, May 7, 1942, until definite information to the contrary is received.”

Hoping the Japanese Government would communicate a list of prisoners of war in the future, the letter specified, persons would “be notified by this office in the event his [brother’s] name is contained in the list of prisoners of war.” The department also warned, persons known to have been present in the Philippines and not reported as “prisoners of war by the Japanese Government, the War Department will continue to carry them as ‘missing in action’…until twelve months have expired.” Rather vaguely, the department spelled out that after the twelve months expired, “in the absence of other information the War Department is authorized to make a final determination.”

The letter ends with information regarding legislation approved for allotments to military personnel’s dependents while being classified as “missing”.

Why White’s brother received this letter is unknown, or how he may have been notified his brother was safe is uncertain. Roy White had shipped out of the Philippines on 28 Oct. 1939 and arrived in on an army base in the U.S. on 18 Nov. 1941.

NPRC Archive Room – Hints & Links

In promotional materials, the NPRC advertises the center is “more than an archival facility; it’s a treasure chest of historic documents that tell the stories of America one file at a time.” I found this to be true. The files contain valuable documentation in the lives of those who served. [1]

When visiting the research room, you are allowed to bring in a scanner or photographic equipment. In attempting to safeguard the records, papers in the files must be kept in the original order they are found and archival staff watch while you view all materials. If papers are stapled or folded the staff will offer assistance to you allow a clearer view of the documents.

I did not feel intimidated by being observed, and at times, unsolicited, they would even come over to help with a difficult paper to unfold. The objective is to protect a valuable resource for generations to come. It really was impressive how they take care of our national heritage.

The staff at the NPRC were friendly, and at least in my case, went out of their way to be helpful and willing to assist me in any way they could.

The public has direct access to archival records.

Archival civilian records, or Civilian Official Personnel Folders (OPFs) of former Federal civilian employees whose employment ended before 1952. NPRC website lists the specific civilian agency records. [2]

Archival military records, or Official Military Personnel Files (OMPFs) of veterans who separated from service before 1955.

OMPFs can be requested for viewing in NPRC Archival Research Room or request for copies via mail by filling out a Standard Form (SF) 180. When making a request, NPRC requires such basic information as a veteran’s complete name, service number, branch of service, date and place of birth, or dates of service. You can even request records online with the ability to check the status of your request using an “Online Status Update Request Form.” [3]

Complicating the availability of some military files, is damage caused by a devastating fire in 1973. The NPRC estimates Army personnel discharged from November 1, 1912 to January 1, 1960 suffered an 80% loss. Air Force personnel discharged from September 25, 1947 to January 1, 1964 a 75% loss. Attempts by NPRC have been made to photocopy some of the damaged records from the 1973 fire. [4]

[1] “The National Archives at St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch Advertising Dept., commemorative issue, October 2011, pg. 2.

[2] Agency listings, “Official Personnel Folders (OPF), Archival Holdings and Access,” https://www.archives.gov/st-louis/archival-programs/civilian-personnel-archival.

[3] “Official Military Personnel Files (OMPF), Archival Records Request,” https://www.archives.gov/st-louis/archival-programs/military-personnel-archival/ompf-archival-requests.html

[4] “The 1973 Fire, National Personnel Records Center,” https://www.archives.gov/st-louis/military-personnel/fire-1973.html,